The Biological Laying Cycle of the Laying Hen: Genetic Improvement and Physiological Limitations

The biological laying cycle of the laying hen is a highly relevant topic in the poultry industry, as it combines aspects of genetics, physiology, nutrition, and management to maximize egg production. Over the decades, genetic improvement and advances in nutrition and management have optimized this process. However, there are physiological limits that prevent a hen from laying an egg every day on a sustained basis.

ANIMAL PRODUCTION

3/4/20255 min read

The biological laying cycle of the laying hen is a highly relevant topic in the poultry industry, as it combines aspects of genetics, physiology, nutrition, and management to maximize egg production. Over the decades, genetic improvement and advances in nutrition and management have optimized this process. However, there are physiological limits that prevent a hen from laying an egg every day on a sustained basis. This article explores the biological laying cycle, the impact of genetic improvement, physiological limitations, and common myths associated with this topic.

The Biological Laying Cycle of the Hen

The life cycle of a laying hen is marked by clearly defined stages, each with its own challenges and requirements:

1. Rearing Stage (0-18 weeks):

During this phase, pullets develop their reproductive system and reach an adequate weight for sexual maturity.

Proper nutrition, with correct levels of proteins, vitamins, and minerals, is essential to ensure optimal development.

Environmental management, including temperature and lighting, also influences growth and preparation for laying.

2. Onset of Laying (18-22 weeks):

Hens begin to lay eggs, although irregularly at first.

Maturation of the reproductive system is key to achieving stable production.

3. Peak Production (25-35 weeks):

During this period, hens reach maximum efficiency, with laying rates close to 95%.

Egg quality (size, shell thickness, and nutritional content) is also optimal during this phase.

4. Stable Production Phase (35-70 weeks):

Production remains high, although with a slight gradual decline.

Proper management of feeding and environment is crucial to prolong this phase.

5. Decline and Retirement (70+ weeks):

The laying rate decreases significantly, and hens are retired from production.

At this point, the birds may be used for other purposes, such as processed meat production.

Genetic Improvement in Commercial Lines

Genetic improvement has been fundamental in increasing the productivity of laying hens. Modern commercial lines, such as Lohmann, Hy-Line, and ISA Brown, are the result of decades of artificial selection and controlled crossbreeding. Some of the most notable achievements include:

Higher Laying Rate:

Modern hens can produce more than 320 eggs per year, compared to 150-200 units laid decades ago.

This has been achieved by selecting birds with greater ovarian capacity and better synchronization of the reproductive cycle.

Feed Efficiency:

Modern hens convert feed into eggs more efficiently, reducing costs and environmental impact.

This has been achieved by selecting birds with more efficient metabolisms and better nutrient absorption.

Greater Productive Persistence:

Modern hens can maintain stable production over a longer period, increasing farm profitability.

This has been achieved by selecting birds with slower reproductive aging.

Disease Resistance:

Genetic improvement has enabled the development of birds more resistant to common diseases, reducing the need for medications.

This has been achieved by selecting birds with more robust immune systems.

Physiological Limitations in Egg Production

Despite advances in genetics and management, there are physiological limits that prevent a hen from laying an egg every day on a sustained basis. These limitations include:

Egg Formation Time:

The process of forming an egg takes between 24 and 26 hours, making it impossible for a hen to lay more than one egg per day.

Additionally, the cycle is not always perfectly synchronized, which can result in slightly longer intervals between eggs.

Energy Expenditure:

Egg production is an energy-intensive process, especially in shell formation, which requires large amounts of calcium.

An unbalanced diet can lead to decreased production and health problems in hens.

Light and Rest Cycle:

Hens require an adequate photoperiod to maintain egg production but also need rest periods to recover.

Constant exposure to light can cause stress and reduce productivity.

Aging and Reproductive Decline:

As hens age, their reproductive capacity declines, leading to a drop in laying rates after 12 to 18 months of production.

Anatomical Limitations:

The reproductive system of hens has a physical limit, and forcing excessive production can cause health problems, such as prolapses or reproductive fatigue.

The Role of Nutrition and Management

In addition to genetic improvement, nutrition and management are crucial to maximizing the productivity of laying hens. Some key aspects include:

Nutrition:

A balanced diet, rich in calcium, proteins, and vitamins, is essential to maintain a high laying rate.

Supplementation with specific nutrients, such as omega-3 fatty acids, can improve egg quality.

Management:

Control of lighting, temperature, and space is critical to maximizing efficiency without compromising animal welfare.

Proper management also includes disease prevention and stress management.

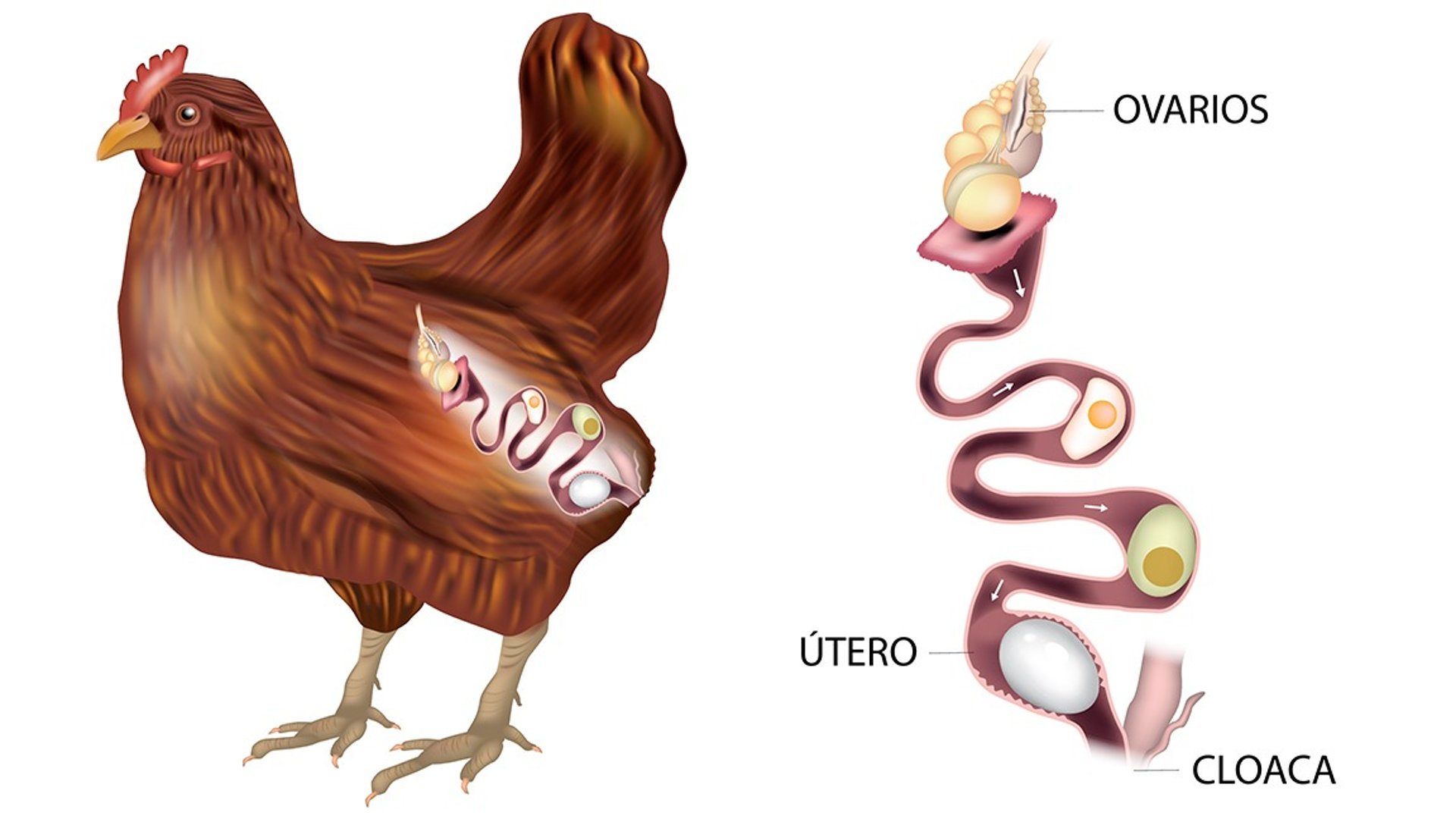

Description of the Egg Formation Stages in Laying Hens

The formation of an egg in laying hens is a complex biological process that occurs in the hen's reproductive system. This process, known as oviposition, takes approximately 24 to 26 hours and is divided into several clearly defined stages:

Ovulation (0 hours):

Egg formation begins with ovulation, which is the release of an ovum (yolk) from the hen's ovary.

Time: This process is almost instantaneous and marks the start of the egg formation cycle.

Infundibulum (15-30 minutes):

The released yolk is captured by the infundibulum, where fertilization can occur if a rooster is present.

Time: The yolk remains in the infundibulum for approximately 15 to 30 minutes.

Magnum (3 hours):

The yolk moves to the magnum, where the egg white (albumen) is secreted.

Time: The yolk remains in the magnum for approximately 3 hours.

Isthmus (1.5 hours):

The developing egg passes to the isthmus, where the inner and outer shell membranes are formed.

Time: The egg remains in the isthmus for approximately 1.5 hours.

Uterus or Shell Gland (18-20 hours):

The egg enters the uterus, where the hard shell is formed and pigments are added.

Time: The egg remains in the uterus for approximately 18 to 20 hours.

Vagina (Few minutes):

The egg moves to the vagina, where it is coated with a protective layer called the cuticle.

Time: The egg remains in the vagina for only a few minutes.

Laying (Less than 1 minute):

Finally, the egg is expelled through the cloaca in a process known as laying.

Time: Laying is almost instantaneous, lasting less than 1 minute.

Common Myths About Laying Hens

There are several myths surrounding laying hens that can lead to misunderstandings or inappropriate practices. Below, some of the most common myths are debunked:

"Hens need a rooster to lay eggs":

False. Hens lay eggs naturally as part of their reproductive cycle, regardless of the presence of a rooster.

"Hens can lay an egg every day without rest":

False. The process of forming an egg takes between 24 and 26 hours, making it impossible for a hen to lay an egg every day consistently.

"Free-range hens lay more nutritious eggs than those from industrial farms":

False. The nutrition of the egg depends on the hen's diet, not the farming system.

"Hens lay eggs throughout their entire lives":

False. Hens have a limited productive cycle, typically 12 to 18 months.

"Hens need constant artificial light to lay eggs":

False. Hens require an adequate photoperiod but also need periods of darkness to rest.

"Larger hens lay larger eggs":

False. Egg size depends more on genetics, age, and nutrition than on the hen's size.

"Hens can lay eggs of unusual colors based on their diet":

False. The color of the eggshell is genetically determined.

"Hens do not need additional calcium to produce eggs":

False. Eggshell formation requires large amounts of calcium.

"Hens can lay eggs indefinitely if given hormones":

False. The use of hormones in egg production is prohibited and cannot overcome the physiological limits of hens.

"Laying hens are not suitable for meat":

False. Although not optimized for meat production, laying hens can be used for processed meat products.

Conclusion: A Balance Between Productivity and Physiology

The biological laying cycle of the laying hen is a complex process that has been optimized through genetic improvement and advances in nutrition and management. However, there are physiological limits that prevent a hen from laying an egg every day on a sustained basis. These limits are determined by the time required for egg formation, energy expenditure, and the hens' need for rest and recovery.

As the poultry industry continues to evolve, it is essential to balance productivity with animal welfare and sustainability. Respecting the biological limits of hens is not only crucial for their health but also for ensuring ethical and sustainable egg production in the long term. Additionally, it is important to debunk common myths surrounding laying hens, as these can lead to misunderstandings and inappropriate practices.

Education and the dissemination of scientifically based information are key to promoting a responsible poultry industry. By understanding and respecting the biological processes of hens, we can ensure their welfare is prioritized while maximizing productivity in a sustainable manner.

AgroPetEd

Information about animals and agricultural practices

© 2025. All rights reserved.